Hello, fellow ghost reader!

And a merry Christmas to you! I hope you’re filled with festive cheer and eggnog!🎄🪩

In anticipation of the inevitable drunkenness/food coma I have queued up this - my little Christmas present to you, loyal subscriber - the essay I wrote and submitted for the animal theory module I took as part of my Master’s degree. (You may remember I’ve written a couple of pieces based on the ideas I was having from that module - Dickensian Dinosaurs and Talking Horses, if you’re interested.)

I found this essay so hard to write (as I did all the assessments I submitted that year. Burnout’s a bitch), and I don’t think it turned out quite how I wanted it to (mainly as a result of writing the better part of this the night before while watching Toast of London, and submitting it at 8am the morning of). However, it was also the best mark I got for that degree, so what the hell do I know? Plus, it’s still fun to think about posthuman toads and Wind in the Willows is a classic, so I figured it would make a good yuletide newsletter, and a fitting reward for all the support I’ve had here since I started this lil publication a couple of months ago.

Enjoy!

A ghost reader 👻

Cyborg Bodies, Transgressive Movement and Toad’s (Death-)Drive for Self-actualisation in 'The Wind in the Willows'

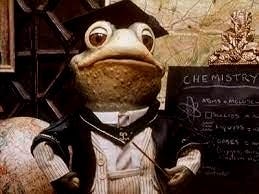

Even now, over one-hundred years after Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows1 was first published, the image of Toad of Toad Hall haring through the countryside in his red motorcar remains ubiquitous within children’s literature. Symbolic of the carefree child,2 the speed of advancing technology,3 and the unstoppable crawl of modern society into the natural world,4 Toad’s ‘wild’ (and illegal) escapades into the world of mechanised travel embodies, to him at least, ‘poetry of motion’. This is a peculiarly apt phrase for the function of the motorcar (technology more widely) and its relationship to the animal form. For Toad, the mechanical physicality of the car, which lends Toad a greater freedom of capability than his amphibian body would otherwise allow, is elevated to the cerebral form of poetics, transcending the physical body and offering access through language - a much less distinct boundary than those presented by corporeal forms, liable to collapse and merge. These boundaries become increasingly troubled for Toad as he sinks ever deeper into his obsession, alienating him from his friends and from the natural spaces and structures of Grahame’s arcadia. Certainly, this goes some way explaining the strange, silly, hilarity of the idea of a toad driving a car, and there is historical precedent for, both the absurdity of the image, and its preposition as a threat to nature and spiritual wellbeing. Traditionally a figure of superstition, the literary, mythic toad is associated with unenlightened concepts of rebirth, transformation, trickery,5 jealousy (sexual and financial),6 ‘the unpleasant journey the body must take after death’, and an ‘agent of evil’.7 As the arrogant, careless, Toad of Toad Hall, then, the toad body feels appropriate, and despite being a largely likeable character it is easy to view his narrative presence as an embodiment of, if not pure evil, then chaos, whose every act of blustering violence leads to destruction and disorder which his sensible friends must patiently set right. It would be easy, therefore, to conclude that the toad/car imagery renders an initially alarming and uncanny depiction of ignorant magical belief at the helm (or should that be wheel?) of new-age technological advancement, and certainly this seems to be the dominant assumption made by critics who fail to find in Toad any redeeming qualities (at least so far as they manifest within the world of the text). The best that can be said is that he is a transgressive character, but it is difficult to think of this in a positive light while also acknowledging that what Toad is transgressing is an Edwardian rendition of a literal Arcadia (albeit, one rooted in patriarchy and the British class structure).8 However, beyond the text’s own morality, and with the benefit of 21st century hindsight, it is difficult to call Toad ‘transgressive’ and accept blindly that this is a bad thing, and it is the purpose of this essay to explore whether Toad’s chaotic escapades in his motor car might not actually be considered radical by examining Willows through the theoretical construct of the cyborg. Using the concepts set forth in Donna Haraway’s Cyborg Manifesto,9 this essay aims to first explore the nature of the cyborg-Toad body, the boundaries it compromises, and the means by which this is actualised, before ultimately considering the implications to Toad’s self in order to demonstrate what exactly these contrivances are doing for both Toad and the wider text, and how these notions demonstrate an accelerated teleology which must integrate the animal and the technological.

Form and Metamorphosis

Considering, first, the body of the cyborg-Toad. As Haraway famously described, biology and evolutionary theory have ‘reduced the line between humans and animals to a faint trace re-etched in ideological struggle or professional disputes between life and social science’, just as mass mechanisation of the 20th century ‘have made thoroughly ambiguous the difference between natural and artificial, mind and body, self-developing and externally designed, and many other distinctions that used to apply to organisms and machines’.10 She argues that Western discourse fundamentally revolves around phallogocentric and dualistic structures which rely on the identification of a definable entity (or ‘self’) and its stratified other (nature/culture, organic/artificial male/female, right/wrong, to name a few). The cyborg stages a rejection of such dichotomy, instead manifesting a kind of corporeal dualism or hybridisation represented physically in mechanical/human/animal forms and extending to encompass all forms of essentialism or naturalism within Western ideology (such as class and gender, among others). This is the dawning space into which our Edwardian Toad steps, but before we consider its implications we must first examine the nature of the cyborg-Toad and the point of his manifestation.

On the one hand, it feels almost obvious that Toad’s sequential fixation (even fetishisation) on ever faster, more autonomous forms of travel represent a post-human desire to increase or extend the relatively limited capabilities of his toad body, something which is supported by the text with the distinct lack of physical representation prior to the motorcar being introduced. This is, to some extent, true of most of the Willow’s characters, and there is an argument to be made that the transparent naming system (by which a mole is named Mole, and so forth) translates obliquely to a physical description - after all, what is the sense in describing a mole when presumably the audience know what a mole looks like? But there is still more of an emphasis on the physical characteristics of the other characters than there is on the toad body. Mole’s snout, paws and fur are at least mentioned in the first moments of our meeting him, as well as his sartorial attire,11 and the same is true for Rat and Badger. But when we meet Toad his physicality is entirely obscured. It is easy to ignore this given that we know he is a toad and so therefore must bare a toad’s physical traits, but it becomes slightly strange when his ‘paws’ (as opposed to the webbed hands or feet characteristic of amphibians) are insidiously introduced,12 and later in the text when he has inexplicably grown ‘hair’ - a distinctly human trait, being opposed to fur (which toads do not have anyway), and also in that he brushes it.13 At the very least, the physical context of Toad’s body is deeply confused, but in a way which may go unnoticed in a text in which the characters, it is often noted, are ‘At once beast and human, small and large [moving] easily between radically discontinuous positions’.14 However, in the context of post-human impulse, Toad’s comparative lack of, and confusion around, form point towards a body that relies on external context for physical realisation.

Cynthia Marshall emphasises the importance of the reader’s empathy for the animal characters which Grahame produces so successfully ‘that on those rare occasions when the beastly status of a character does receive explicit mention, we feel our own senses expanding to encompass the experience’. This is possibly true of the animal experience more broadly, but when it comes to expanding the experience of the reader into the specific experience of the toad by the measure of his physicality alone, this is simply impossible to sustain since whatever ‘toadliness’ he may possess is almost never present on a textual level. Moreover, strange and un-toadlike though they may be, these references to Toad’s physical attributes (his paws and hair, as well as all other facets of his toad body) only begin to appear after the motorcar has entered the narrative.15 Before this happens it is the caravan, ‘shining with newness, painted a canary-yellow picked out with green, and red wheels’,16 which forms the dominant (indeed, the only) realised body during our first interaction with him. Suddenly, with the arrival of the motorcar, Toad’s body begins to materialise within the narrative. By chapter six - well into his ‘motorcar-phase’, now being upon his seventh car having already bought (and destroyed) six - Toad is resplendent ‘arrayed in goggles, cap, gaiters, and enormous overcoat, came swaggering down the steps, drawing on his gauntleted gloves’.17 Where, before, Toad exists and moves through the space of the text in a phantasmical way (in that it is never explicit), now he ‘swaggers’ as a defined form which we are able to visualise. When his friends attempt their intervention to divest him of his motorcar body they begin (perhaps astutely) by forcibly stripping him of his driving attire in an act of intimate (if not explicitly sexual) aggression. Having privately ministered to Toad on the ills of his behaviour, Badger then reproduces the naked, ‘very limp and dejected’ Toad, whose ‘skin hung baggily about him, his legs wobbled, and his cheeks were furrowed by the tears so plentifully called forth by the Badger’s moving discourse’.18 Toad’s natural body, having been separated through physical and discursive force from the trappings of the motorcar, emphasises organic texture in stark opposition to the ‘shiney new motorcar’. This scene provides some explanation for Yarbrough’s depiction of Toad ‘shallow’, dandified aesthete, for which he claims Grahame condemns him.19 Afterall, it is a reasonable conclusion to come to having seen how his clothes are so easily removed and the mottled skin of a toad is exposed beneath. But Toad rejects his grotesque debasement and proves that his motorcar-self is still present, even without sartorial emphasis, as Rat perceives the ‘twinkle in [Toad’s] still sorrowful eye’, emulating the motorcar’s ‘shiny’ body and directly preceding his refusal to disavow his obsession.20 It is at this point that we realise and accept his various bodies - first his un-toad-like animal/pseudo-human form, then his proximity to the motorcar body, and finally the toad - which in this moment, all collapse into one toad.

This is supported by Toad’s final statement of stubborn transgression. He insists he will not apologise for his actions - ‘On the contrary, I faithfully promise that the very first motor-car I see, poop-poop! off I go in it!’21 This is significant beyond his defiance, and speaks (literally) to the point of contact and metamorphosis within the toad body. Despite the group’s forceful confrontation, Badger resorts to private dialogue as a means of getting Toad to see sense, stating ‘I’ll make one more effort to bring you to reason. You will come with me into the smoking-room, and there you will hear some facts about yourself; and we’ll see whether you come out of that room the same Toad that you went in.’ The pair disappear, leaving Rat and Mole alone we are told for ‘some three-quarters of an hour’, listening to ‘the long continuous drone of the Badger’s voice, rising and falling in waves of oratory; and presently they noticed that the sermon began to be punctuated at intervals by long-drawn sobs, evidently proceeding from the bosom of Toad’.22 Toad’s naked body is ‘limp’, ‘baggy’ and ‘wobbling’ as a result of discourse, inaccessible to the narrative as our focus remains with Mole and Rat who are excluded from the conversation. Grahame’s decision to reduce Badger’s speech to undefined ‘rising and falling [...] waves of oratory’, natural in it’s gentle undulations (perhaps even reminiscent of the sounds from the riverbank), transforms Badger’s discursive skills mimic the pastoral idyll, disrupting Toad’s body from which ‘long-drawn sobs’ are elicited. But, more interesting here is how we see language and speech are situated within the text’s dyadic structures, which David McCooey and Emma Hayes argue are established in order to access a liminality which thus allows for ‘heightened or transformed perception’.23 We will return to this concept momentarily, however, we must acknowledge that, in this case, sound and voice are able to traverse the compromised space separating nature (Toad’s body) and technology (the motor car), and affect a temporary separation. However, the spell is undone just as easily when Toad proclaims ‘I’m not sorry!’24

Momentarily leaving aside from the transformative properties of speech, Toad does not approach or navigate communication in the same way his other animal friends do - that is to say honestly. Mole, Rat and Badger communicate plainly, stating what is (at least as they perceive it). When they stage their intervention, Badger’s approach is to subject Toad to ‘hear[ing] some facts’ about himself which he believes will be enough to convince Toad to change his ways.25 Here, it is important to consider the differences between the transformative nature of Toad’s own speech (which his peers would no doubt take for lies), and the honest, descriptive speech of his friends. Where Badger aims to use his metamorphic powers of oration to, in the words of Rat, ‘convert’ Toad,26 Toad’s speech also has transformative powers through the various fantasies, identities and general untruths he creates. Yarbrough’s observation that ‘Toad accumulates language and imagined visuals [...] the way he accumulates cars’ identifies Toad’s tendency towards drama in his speech patterns as a means of constructing masculinity.27 Naturally, there is an incredibly gendered aspect to the assumption of the car body. Through the motorcar, Toad is able to affect a quixotic and performative masculine heroism with the motorcar functioning as the symbolic phallus. As he speeds about the country, constructing his own mythology through balled verse,28 Toad in his motorcar begins to parody the brave knight on his noble steed.29 Toad himself acknowledges this, again, through inconsistent cyborg linguistics as he turns to mock-romantic to conceptualise his motorcar self: ‘O what a flowery track lies spread before me, henceforth! What dust-clouds shall spring up behind me as I speed on my reckless way!’ he cries.30 However, his chivalric impulse is not solely constrained to mechanical dualism. As he contemplates the prospect of becoming the washerwoman in order to escape imprisonment, ‘Toad, between his sobs, [...] reflected, and gradually began to think new and inspiring thoughts: of chivalry, and poetry, and deeds still to be done’. The goal of all transformation, be it mechanical, gendered or class-based, corresponds to the desire to perform heroism. As such the performance of a working-class woman, also doubles as the performance of the knight atop his brave charger.

This gestures towards the importance of the gaze upon the body and the purpose of performance which we have already touched on. During his time as the washerwoman, he is beholden to the same essentialist perceptions that the animal community categorise themselves by - just as Toad is called Toad because he is a toad, the washerwoman is simply a washerwoman, as opposed to an individual identity that an actual name implies; ‘I am a poor unhappy washerwoman’,31 he cries, and the world replies ‘Hullo, washerwoman!’32 In much the same way as language mediates his vacillation between motorcar and amphibian, Toad becomes the washerwoman he pretends to be by taking advantage of the assumption of what we might term ‘descriptive’ language. In many ways this harks back to the superstitious toad body and its connection to transformation, trickery and rebirth as Toad's superpower lies in his ability to transform liminal discourse between form into realised physicality. Certainly, there can be no other reason that a toad could pass for a human woman, and indeed he does not once he acknowledges his true Toad self at which point he plainly reverts to a toad in the eyes of those perceiving him. This is not to assume, however, that the general perception of Toad as a dishonest ‘liar’ is (entirely) correct. Indeed, though his speech is certainly deviant, it is more accurate to describe Toad’s speech as ‘creative language’ - that which actualises form and identity simply through its expression. Indeed, Lois R. Kuznets asserts that a key theme the novel implicitly supports is the anxiety at a ‘woman's dangerous power to limit man's freedom’,33 which is certainly the case for the majority of male-animal characters, but Toad’s performance as a woman proves exactly the opposite by providing the means by which he might find his freedom. In this way, Toad’s famous compulsive ‘Poop-poop!’ - which, like his twinkling eye, is a cyborgian characteristic that cannot be prevented simply by undressing him or preventing him from driving - is arguably his most transgressive act in that it persists without the necessity of an audience to believe the totality of identity - it is not blindly accepted as his experiments with female and working-class identities are. Cyborg-Toad instead suffers rejection in a bid by his peers to restore order. ‘He is now possessed. [...] He'll continue like that for days now, like an animal walking in a happy dream, quite useless for all practical purposes. Never mind him’, proclaims a withering Rat,34 dismissing Toad’s manifested self as ‘possession’ rather than identity, and relegating the motorcar to the realm of fantasy which is not worth his acknowledgement.

Interestingly, criticism has largely responded to Toad on these terms, rather than accepting his capacity for change. This is certainly tempting, as in doing so we are not forced to reconcile his many faces and identities - it is easier to conclude that, while Toad’s various performances may give him a chance to experiment with different, ultimately worse off, identities to his own, he remains fundamentally the bumbling, privileged aristocrat who’s assumption of these roles is nothing more than an act of tourism into marginalised personae. This conclusion, however, does a great disservice to Toad’s unique approach to the construction of his own identity through language. It is a mistake for us to wilfully misunderstand him, when his own dialogue around his identity is constructed to be misunderstood. Cyborg-Toad’s assumption of identity (mechanical and otherwise) is akin to Judith Butler’s famous conception of the performance of gender and drag - that all gender is performance and drag is simply a self-aware performance.35 Just as Haraway describes, Toad’s cyborg identities muddy the boundaries between animal/human/machine and stage them as drag - self-conscious reproductions of themselves which collapse their own boundaries simply by acknowledging their presence. As such, the reader should consider his performances no less real simply because they are performed. Toad’s speech creates an avenue through the rigid structures the text’s characters desperately enforce, and raise them from the liminal, and thus insubstantial, properties of speech to give them actualised form.

Evolution/Degeneration

There is a final aspect of Toad’s body and his self-determination which we have yet to acknowledge. Having assumed the body of the car as his own, Toad’s journey accelerates (pun intended). As we have discussed, the car on the most basic level functions as an extension of Toad’s amphibian form, drawing his natural body out from under its superstitious past and into the shiny promise of Edwardian society. The movement of this happens very tangibly within the text, both in Toad’s literal movements through space, and within the function of the metaphorical aspects of the narrative, and it is to this which we now turn our attention to investigate the cyborg-Toad as a figure characterising and caricaturing human ‘progress’, and ask whether he is evolving or degenerating.

At the zenith of his caravan-phase Toad dismisses boating as a ‘Silly boyish amusement’. He has given it up, he proclaims, ‘long ago’, having concluded it is a ‘Sheer waste of time’, commiserating with Rat and Mole in their ignorance of better means of transportation, despite having moved on from it so quickly that Rat does not even realise it is over. ‘It makes me downright sorry to see you fellows, who ought to know better, spending all your energies in that aimless manner,’ he declares.36 In this, we see Toad’s desire to experience ever faster and wider movement is intersected by the axis of time. Time is ‘wasted’ on lesser means of transport whose movement, like the boat confined to the river bank, is restricted. Removing it from recognised ‘progress’ and transforming it into a ‘boyish amusement’ of ‘long ago’, Toad situates the boat in a constructed past within his teleology. Space and the individual's capacity to fill or pass through it must be maximised and the method of transport is measured by its capacity to first access that space, and second by the speed at which it is able to access it. To continue in such a way when better means of travel are discovered is to effectively go back in time.

There's real life for you, embodied in that little cart. The open road, the dusty highway, the heath, the common, the hedgerows, the rolling downs! Camps, villages, towns, cities! Here to-day, up and off to somewhere else to-morrow! Travel, change, interest, excitement! The whole world before you, and a horizon that's always changing!37

Toad’s caravan is better than the boat because it gives him access to a wider world than the riverbank at greater speeds. Soon after, however, it is surpassed by the motorcar which Toad immediately identifies as

The real way to travel! The only way to travel! Here to-day—in next week to-morrow! Villages skipped, towns and cities jumped—always somebody else's horizon!38

The motorcar not only gives the toad access to the space of the world in a way his animal body would not allow, but also manifests as a kind of time-travel. In a car you can be ‘Here today’ but ‘in next week to-morrow’. Toad’s pursuit of ever improved tools of movement take him farther and faster down ‘the open road’ and the process of a distinctly teleological, distinctly human advancement.

This links to another commonly held interpretation - that of the domestic space as a metaphorical womb. While it is generally approached indifferently, its presence in the text is still slightly uncomfortable as it hovers close enough to offer a place of safety to return to, thus allowing them, on some level, to maintain identification with the mother and remain the relative child, avoiding teleology altogether.39 It is at this point that we must question Marshall’s point that the domestic is intrinsically linked to pleasure.40 Kimball identifies Grahame’s animals with the state of the Romantic child which he states is ‘extended and unnatural’ as it necessitates eternal innocence,41 here enacted through the construction of the home/womb. How, then, can the home truly embody pleasure if it is indeed the tool for maintaining static childhood? McCooey and Hayes construct the home as an absolute entity in the text, arguing that ‘Even the stoats and the weasels have homes, and, as the novel’s ending makes clear, when they keep to those homes, social cohesion is returned’.42 This is particularly interesting in the context of the womb/home which fundamentally seems to offer the liminal experience of existing between life and ‘non-life’ (death). But this is the perception of an adult (which Kimball warns we must be wary of) - to the child, the desire for safety and the mother betrays a fear of danger - of growing up, of the ‘wide world’, of what Toad poignantly refers to as ‘real life’.43 Thus, the child perceives the home to be both an absolute entity (safety), and as such the uncanny sensation of liminality is rendered pleasurable in that it presents an alternative to danger.

This does not hold true for Toad, who’s instinct, instead of pushing him to return to the home, constantly seeks to leave and move farther and farther away from it. This is the crux of what makes the motorcar so appealing to him. Instead of seeking a return to the womb, and thus eternal childhood, Toad’s desire for adventure manifests as a literal death-drive.44 Much like Toad’s insistence upon an outward expression of identity, contrasted with his friends’ consideration over what makes a ‘good’ animal (an internal expression),45 Toad’s journey propels him out and away from the home, seeking adventure and culminating in the collision. Indeed, to collide certainly seems to be the ultimate aim. When put under house arrest, Toad is compelled by ‘violent paroxysms’ to ‘arrange bedroom chairs in rude resemblance of a motor-car and would crouch on the foremost of them, bent forward and staring fixedly ahead, making uncouth and ghastly noises, till the climax was reached, when, turning a complete somersault, he would lie prostrate amidst the ruins of the chairs, apparently completely satisfied for the moment.’46 This is particularly interesting - forcibly separated from an actual car, Toad’s vocal manifestations are ‘made uncouth and ghastly’, and the sexual connotations of this, coupled with his pursuit of a satisfactory ‘climax’ in which he stages a symbolic crash, must be accepted as an act of pleasure. Away from the dual body of the car, Toad manifests his pleasure as an act of manual stimulation but without the extended form of the metaphorical phallus, and as such the act is ironically rendered grotesque and even comical to the reader who wonders at how such an act could be fun, let alone pleasurable. That being said, the primary point of this scene is to make us aware that, unlike his friends, Toad’s pursuit of pleasure is (for want of a better phrase) a ‘grown-up’ one - one that requires a fully realised individuated identity (that is, an identity which can be fully separated from the home and which is manifested on one’s own terms). In short, Toad’s characterisation as a kind of anti-Romantic child - one who is aware of, and curious about, the world beyond the limits of his knowledge - means that he understands true pleasure as a concept which the Romantic child cannot access being as they exist in a state of uncompromised innocence which we might align with the concepts of essentialism. Cyborg-Toad desires to escape from the boundaries that confine his friends and this is nowhere more evident than in the demonstration of the dual act of sex/death that is epitomised by the car crash.

In this way, the teleological act becomes the pleasurable one, but in order for this to be enjoyed repeatedly, Toad must systematically circle back and complete the process of embodiment, excitement, destruction - moving back and forth within, both the narrative space, and along the timeline he constructs for his identity. As such, it would be foolish to think that Toad only represents forward motion. First and foremost, the motorcar is defined by perpetual ‘newness’. Much like the toad’s superstitious body, Toad’s repeated crashes mean that his experience with the motorcar is one of constant renewal as they must be replaced again and again. In this way, it figures that Toad is trying to manifest the motorcar’s double function as one of both increased physical capability, as well as renewed youth, thus effecting a kind of immortality in the motorcar-toad body. We might assume, therefore, that this is just a further extension of the text’s figuration of the Romantic child, which, as Miles A. Kimball sees it, is defined equally by ‘static innocence’, being unable to comprehend the potential loss of it - in other words, the ‘denial of [...] change, evolution, decay and death’.47 Toad’s constant reaffirmations of youth with every new motorcar certainly seem to lack a sense of awareness of the potential danger to life, evidencing the Romantic child.48 This, however, is misleading. While Toad clearly appears (in his external presentation) to be a Romantic child, his internal experience disproves his innocence in its manifestation. As Ratty tells us of Toad’s alarming rate of machine consumption, he divulges that ‘As for the others—you know that coach-house of his? Well, it's piled up—literally piled up to the roof—with fragments of motor-cars, none of them bigger than your hat! That accounts for the other six—so far as they can be accounted for’.49 To the outside world, Toad is destroying and discarding his automobiles before simply replacing it with another - an affirmation of the Romantic child persona which he performs in his external presentation. However, on the inside - that is, inside Toad Hall - the fragmented bodies of his previous ‘lives’ are retained, consuming space, warping the disused coach-house into a monstrous garage of unfixable parts. Afterall, to carelessly and violently destroy the symbolic body over and over is one thing, to then collect the shattered parts and transform the domestic space into a graveyard of their ancestors is quite another.

Returning to the idea of the home/womb construction, it is now pertinent to conclude that Toad Hall is an outlier in that it fails to align itself categorically with the female body. Unlike the holes and burrows of his friends, Toad Hall is not a cosy place. It is a space more closely connected to the farther and the ancestral, aristocratic right of primogeniture. It has come to Toad as a means of connecting with and sustaining ancestral lineage - essentially an act which is parodied by Toad’s cycle of acquiring, destroying and then retaining the fragmented (‘dead’) motorcar within the walls of the house. This too, represents a kind of teleological movement of identity, but one which is fixed (literally built) in space, necessitating its constant expansion to accommodate the new and facilitate the conquering of new territories. Toad initially builds a boat house to accommodate his boating obsession,50 then the stable is occupied to integrate the caravan and all of the new possibilities it offers.51 These spaces are ultimately left useless due to the speed with which Toad races to access more of the world, and are either co-opted in order to integrate the new, or abandoned entirely. Kuznets senses a similar discomfort in Toad Hall, arguing that it lacks a ‘some core of intimacy’, which Gaston Bachelard describes as being central to the concept of the home. Kuznets sees this as an instability,52 which we agree is an accurate way of describing this ever growing, ancestral behemoth, particularly since it is filled with the bodies of those ancestors (the fragmented motorcar representing the past self, which references the ancestral figure) and requires even faster growth is struggling to hold them. In this way, the death-drive of the cyborg-Toad is mirrored in the function of the estate, since, as we have discussed, the act of collision alludes to the sexual act, which, in terms of the ancestral estate, ensures both the safety of lineage and threatens its untimely end. This mirroring between Toad and Toad Hall highlights the fundamental tension with which we approach Toad, as one who’s identity seems both constantly reverting to an archaic version of the self, but also projecting forward in the name of continuation and progress.

Fundamentally, the presence of the cyborg-Toad cannot be judged by moral frameworks (though his friends certainly try). He is a neutral agent of chaos whose only aim is to stage acts of contact and through collision - the pleasurable culmination of teleological progress and the thing which threatens its absolute end from which the body may not be resurrected causing the self to revert back to an earlier, more naive self. Just as none of this can be said to be distinctly negative, it also surely is not positive, as Toad’s extension of form is absolutely one of violence and danger. However, we must ultimately recognise that movement is transgressive, and even radical act in Willows because it rejects the stasis which the other characters have confined themselves to, risking safety in favour of self actualisation, pleasure and egalitarian contact.

Kenneth Grahame, The Wind in the Willows (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2023).

Miles A. Kimball, ‘Aestheticism, Pan, and Edwardian Children’s Literature’ CEA Critic, 65.1 (2002), 50-62 (pp. 52) <https://www.jstor.org/stable/44377555> [accessed 23 February 2024].

Sarah Gilead, ‘The Undoing of the Idyll in the Wind in the Willows’ Children’s Literature, 16.1 (1988), 145-158 (pp. 148) <http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/chl.0.0660> [accessed 23 February 2024].

J.R. Wytenbroek, ‘Natural Mysticism in Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows’ Mallorn, 33.1 (1995), 431-434 (pp. 432) <https://www.jstor.org/stable/45320464> [accessed 24 February 2024].

Marty Crump and Danté Bruce Fenolio, Eye of Newt and Toe of Frog, Adder's Fork and Lizard's Leg: The Lore and Mythology of Amphibians and Reptiles (Chicago: University of Chicago Press). Google Books ebook.

Doris Adler, ‘Imaginary Toads in Real Gardens’, English Literary Renaissance, 11.3 (1981), 235-260 (pp. 236) <https://www.jstor.org/stable/43447298> [accessed 1 March 2024].

Mary E. Robbins, ‘The Truculent Toad in the Middle Ages’, in Animals in the Middle Ages ed. by Nona C. Flores (London: Routledge, 2016), (n.p.). Google Books ebook.

Jane Darcy, ‘The Representation of Nature in The Wind in the Willows and The Secret Garden’, The Lion and the Unicorn, 19.2 (1995), 211-222 (p. 212) <https://doi.org/10.1353/uni.1995.0018> [accessed 2 March 2024].

Donna Haraway, The Cyborg Manifesto (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2016). Ebook Central ebook.

Haraway, p. 10-11.

Grahame, p.1-2.

Grahame, p.36.

Grahame, p. 181, 248.

Cynthia Marshall, ‘Bodies and Pleasures in The Wind in the Willows’, 22.1 (1994), 58-68 (p. 60) <http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/chl.0.0454> [accessed 1 March 2024].

The first mention of his ‘paws’ comes just after the motorcar appears and damages the caravan: having shaken himself out of his motorcar stupor ‘Toad caught [Rat and Mole] up and thrust a paw inside the elbow of each of them’. All physical references to Toad in the text eschew from here. Grahame, p. 36.

Grahame, p. 25.

Grahame, p. 103.

Grahame, p. 106.

Wyne Yarbrough, ‘Animal Boys, Aspiring Aesthetes, and Differing Masculinities: Aestheticism Revealed in The Wind in the Willows’ in Kenneth Grahame's The Wind in the Willows: A Children's Classic at 100 eds. by Jackie C. Horne and Donna R. White (Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 2010), pp. 157-86. Google Books ebook.

Grahame, p. 107.

Grahame, p. 108.

Grahame, p. 105-106.

David McCooey and Emma Hayes, ‘The Liminal Poetics of The Wind in the Willows’, Children’s Literature, 45.1 (2017), 45-68 (p. 52) <http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/chl.2017.0003> [accessed 25 February 2024].

Grahame, p. 107.

Grahame, p. 105.

Grahame, p. 103.

Wynn Yarbrough, ‘Boys to Men: Performative Masculinity in English Anthropomorphic Children’s Tales’ (unpublished doctoral thesis, University of Louisiana, 2007) p. 55.

‘The world has held great Heroes, / As history-books have showed; / But never a name to go down to fame / Compared with that of Toad!’ It is also interesting to note that, later in his song, Toad refers to himself as a human ‘handsome man’. Grahame, p. 196.

Yarbrough 2007, pp.54.

Grahame, p. 34-35.

Grahame, p. 149.

Grahame, p. 155.

Lois R. Kuznets, ‘Kenneth Grahame and Father Nature, or Whither Blows The Wind in the Willows?’, Children’s Literature, 16.1 (1988), 175-181 (p. 175) <https://doi.org/10.1353/chl.0.0304> [accessed 25 February 2024].

Grahame, p. 35.

Judith Butler, Gender Trouble, 4th edn (London: Routledge, 2010) pp.186-7. Kortext ebook.

Grahame, p. 25

Grahame, p. 25-26.

Grahame, p. 34.

Kathryn V. Graham, ‘Of School and the River: The Wind in the Willows and its Immediate Audience’, Children’s Literature Association Quarterly, 23.4 (1998), 181-186 (p. 182) <https://doi.org/10.1353/chq.0.1154> [accessed 3 March 2024].

Marshall, p. 60.

Kimball, p. 53.

McCooey and Hayes, n.p.

Grahame, p. 25.

The idea that all organic matter, on some level, desires to return to an in-organic state (death), This manifests as aggression and destructive behaviours. Sigmund Freud, Beyond the Pleasure Principle, (London: Hogarth Press, 1920). Google Books ebook.

Badger chastises Toad for squandering his father’s money and his motorcar obsession: ‘you’re getting us animals a bad name’. Grahame, p. 105.

Grahame, p. 109.

Kimball, p. 54-58.

Kimball, p. 56.

Grahame, p. 63.

Grahame, p. 23.

Grahame, p. 63.

Lois R. Kuznets, ‘Toad Hall Revisited’, Children’s Literature, 7.1 (1978), 115-128 (pp.) <https://doi.org/10.1353/chl.0.0277> [accessed 6 March 2024]. See also, Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space, (New York: Beacon Publishing, 1994) pp. 29.

Bibliography

Adler, Doris, ‘Imaginary Toads in Real Gardens’, English Literary Renaissance, 11.3 (1981), 235-260 <https://www.jstor.org/stable/43447298> [accessed 1 March 2024]

Bachelard, Gaston, The Poetics of Space, (New York: Beacon Publishing, 1994) pp. 29.

Butler, Judith, Gender Trouble, 4th edn (London: Routledge, 2010) pp.186-7. Kortext ebook

Crump, Marty and Fenolio, Danté Bruce, Eye of Newt and Toe of Frog, Adder's Fork and Lizard's Leg: The Lore and Mythology of Amphibians and Reptiles (Chicago: University of Chicago Press). Google Books ebook

Darcy, Jane, ‘The Representation of Nature in The Wind in the Willows and The Secret Garden’, The Lion and the Unicorn, 19.2 (1995), 211-222 (p. 212) <https://doi.org/10.1353/uni.1995.0018> [accessed 2 March 2024]

Freud, Sigmund , Beyond the Pleasure Principle, (London: Hogarth Press, 1920). Google Books ebook.

Gehling, Madison Noel, ‘Beyond the River Bank: Toad’s Secret Arcadia in TheWind in the Willows’, Journal of the Fantastic in the Arts, 31(3), 341-511 (p. 344) <https://web-p-ebscohost-com.ezproxy-prd.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=0&sid=587f169a-9544-4153-8269-fcbe88437c04%40redis> [accessed 7 March 2024].

Gilead, Sarah, ‘The Undoing of the Idyll in the Wind in the Willows’ Children’s Literature, 16.1 (1988), 145-158 <http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/chl.0.0660> [accessed 23 February 2024]

Graham, Kathryn V., ‘Of School and the River: The Wind in the Willows and its Immediate Audience’, Children’s Literature Association Quarterly, 23.4 (1998), 181-186 (p. 182) <https://doi.org/10.1353/chq.0.1154> [accessed 3 March 2024]

Grahame, Kenneth, The Wind in the Willows (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2023)

Haraway, Donna, The Cyborg Manifesto (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2016). Ebook Central ebook

Kimball, Miles A., ‘Aestheticism, Pan, and Edwardian Children’s Literature’ CEA Critic, 65.1 (2002), 50-62 <https://www.jstor.org/stable/44377555> [accessed 23 February 2024]

Kuznets, Lois R., ‘Kenneth Grahame and Father Nature, or Whither Blows The Wind in the Willows?’, Children’s Literature, 16.1 (1988), 175-181 (p. 175) <https://doi.org/10.1353/chl.0.0304> [accessed 25 February 2024]

— ‘Toad Hall Revisited’, Children’s Literature, 7.1 (1978), 115-128 (pp.) <https://doi.org/10.1353/chl.0.0277> [accessed 6 March 2024].

Marshall, Cynthia, ‘Bodies and Pleasures in The Wind in the Willows’, 22.1 (1994), 58-68 (p. 60) <http://doi.org/10.1353/chl.0.0454> [accessed 1 March 2024]

McCooey, David. and Hayes, Emma, ‘The Liminal Poetics of The Wind in the Willows’, Children’s Literature, 45.1 (2017), 45-68 (p. 52) <http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/chl.2017.0003> [accessed 25 February 2024]

Robbins, Mary E., ‘The Truculent Toad in the Middle Ages’, in Animals in the Middle Ages ed. by Nona C. Flores (London: Routledge, 2016). Google Books ebook

Wadsworth, Sarah, ‘‘When the Cup Has Been Drained’: Addiction and Recovery in The Wind in the Willows’, Children’s Literature, 42.1 (2014), 42-70 (p. 44) <http://doi.org/10.1353/chl.2014.0015> [accessed 3 March 2024]

Wytenbroek, J. R., ‘Natural Mysticism in Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows’ Mallorn, 33.1 (1995), 431-434 <https://www.jstor.org/stable/45320464> [accessed 24 February 2024]

Yarbrough, Wynn., ‘Boys to Men: Performative Masculinity in English Anthropomorphic Children’s Tales’ (unpublished doctoral thesis, University of Louisiana, 2007) p. 55

— ‘Animal Boys, Aspiring Aesthetes, and Differing Masculinities: Aestheticism Revealed in The Wind in the Willows’ in Kenneth Grahame's The Wind in the Willows: A Children's Classic at 100 eds. by Jackie C. Horne and Donna R. White (Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 2010), pp. 157-86. Google Books ebook